I’m making a film about Ralph Waldo Emerson. Yes, that’s the guy you’ve heard of, perhaps know something about. Perhaps you have a distant memory of having to read the essay “Self-Reliance” or, Heaven help you, “Compensation.” You tried, you really did… but then you gave up. “Where the hell is this guy going?” you asked yourself as you slogged through the old man’s paragraphs and his decidedly non-linear progression of thought. That was a proper question on your part. But, in truth, you gave up too soon. My job as a filmmaker is to get you to try one more time after you have seen my film.

To be clear, making a documentary film about Emerson is a tough assignment. Filmmaking is storytelling through the use of moving images. How do you make a film about someone whose primary reason for living was thinking?

Well, you try to make that film by placing him squarely in the context of his time. I am out to prove that Emerson is universally America’s greatest mind by showing how he thought and wrote about the events of his own time. Most notably, his thoughts and writings about that abomination known as slavery. What we learn from that exercise helps to push the monumentality of his genius into our own time, where things are not really much different than they were in Emerson’s day.

There is no substantive human difference between the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 under which horror, in 1851, the escaped slave Thomas Sims was arrested in Boston and returned forcibly in chains to Georgia…and the distinct possibility in our own day that a pregnant teenager might at some time be arrested on the streets of Boston and returned forcibly in handcuffs to bear a child to full term in her home state of Texas.

Emerson wrote and spoke eloquently about the rights that Sims had to his own person. With those words, I say “up again old heart” (which Emerson has taught me), for he has left us a legacy of how to get to the very essence of the possibility of the forced subjugation of a young woman’s very personhood in the modern era. It’s what Emerson is good at: writing and speaking in his own time while casting so bright a light on the business of life that its intensity shines into our own era undiminished. “The ancestor of every action is a thought,” he wrote. You can literally renew the world by thinking about how to do it. If you want to know how I am making a film about someone who spent his days cogitating, I’ve just let you in on the secret.

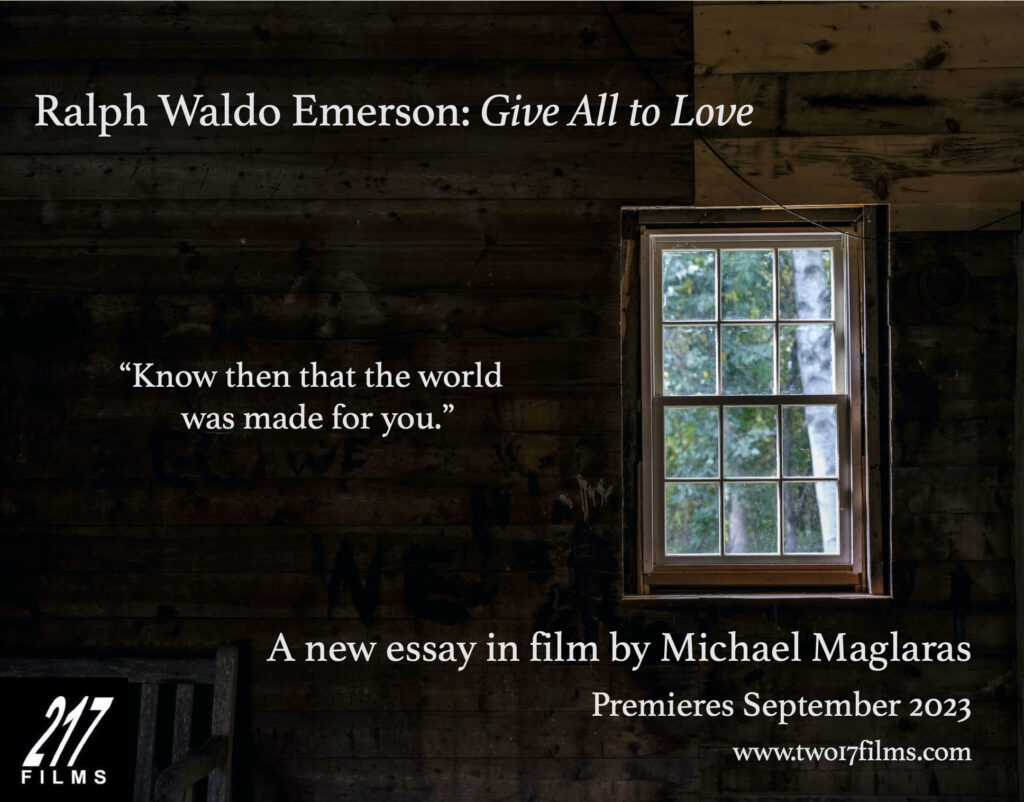

This film is entitled “Ralph Waldo Emerson: Give All to Love.” Yes, the title of one of his poems. You may not associate the Sage of Concord with passion and with passionate feeling, but he’s got it in spades. “Nothing great was ever accomplished without enthusiasm,” he wrote, and Emerson’s love for the world was carried on with an intensity of enthusiasm and belief that is astounding.

“One of the most beautiful compensations in life is that no person can help another without helping themselves,” he wrote. He is the ultimate believer in us, Emerson is. “Know that the world was made for you. For you is the phenomenon perfect.” Emerson the idealist, with the mind of a philosopher and the soul of a poet, pulsing forward, generation by generation, singing the truths that can be revealed by our own cultivation of our relationship to the natural world.

Emerson’s way of approaching life, a loose assemblage of stuff borrowed from here and there which became Transcendentalism, was neither a philosophy nor a religion. It certainly was never a cult. Emerson would not have tolerated it. It was just a way of dealing with and understanding the tangle of existence through the use of all of our faculties. What’s more, Emerson thought so much of us, as individuals, that he was convinced that each of us possesses the spark needed to do all of this on our own with not a bit of help. “Nothing is sacred but the integrity of your own mind,” he would tell us.

Emerson’s Transcendentalism is about self-awareness and self-fulfillment through full and solitary immersion in nature. Solitary people don’t join much…including sometimes not even the human race, but Transcendentalism was essential Emerson, at least for a while. But then there’s more: your achievement of an evolving self-awareness eventually connects you, through your connection to the natural world, with the circularity of existence. You then bring all this stuff that you’ve learned back into the community where you live, thereby expanding and enriching us all. A perfect formula, true…and perhaps a bit simplistic for our own jaded times. I suggest to you, though, that it’s well worth a try. After all, what have we got to lose?

Our shooting schedule in Concord, Massachusetts has taken us deeply into the presence of Emerson and his story. His reconstructed study, lovingly maintained in the Concord Museum, is where my cameraman danced a ballet-like minuet, balancing a Steadicam, while I followed behind him making sure he tripped over nothing. And at Bush, the Emerson homestead, where we filmed sequences over the course of two days, and where, I’m convinced, we encountered ghosts, whose presence seemed somehow comforting…like the creaking floorboards that made my sound man frantic. All of this has been magic. Crawling inside Emerson’s life; sitting in his chair, staring at his books, filming the bed where he breathed his last.

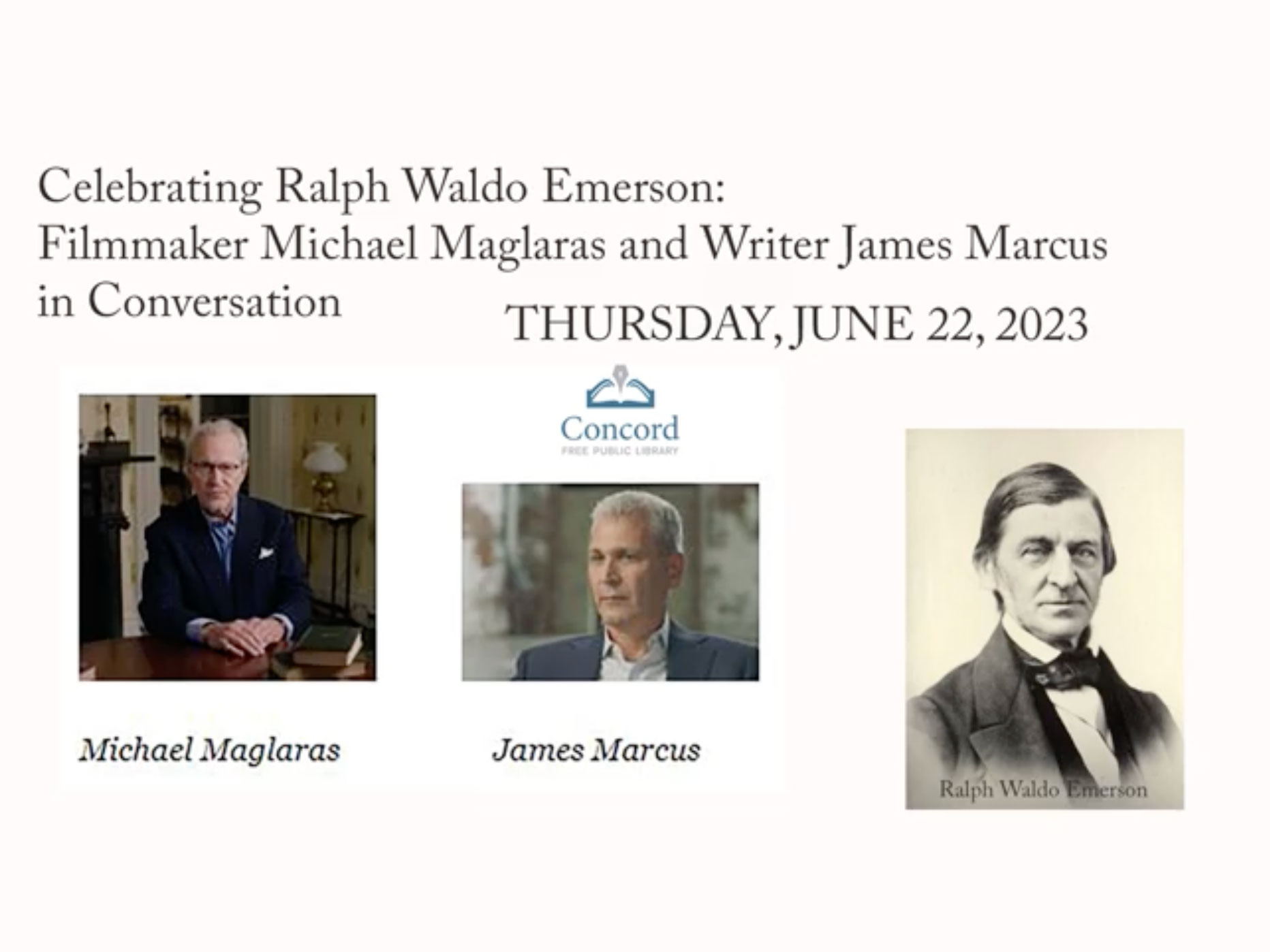

I’m grateful to have the participation of the Emerson scholar and noted writer and editor, James Marcus. James is, I’ve discovered, the ultimate thinking man for our times. James was interviewed for this film. His sequences are stunning. He has also been patient with my many questions and has never shot down any of my Emersonian trial balloons, no matter how spurious my conjectures. He is the foremost living authority, not on Emerson per se, but more importantly on how to think about Emerson. How to absorb him. How to incorporate him into your life. His profoundly important new book on why Our Philosopher is the perfect guide for these troubled times, “Glad to the Brink of Fear,” will be published soon. I have had the privilege of reading this book in one of its earlier iterations. It will do more for the cause of Emerson than we can imagine and is a reason to rejoice.

This has been “a year of living dangerously.” Emerson’s naked, radical, undimmed optimism has infused my home and my professional life. My wife, and muse, and artistic partner, Terri Templeton (who is also my executive producer) and I have spent many evenings debating, discussing, and tossing Emerson’s ideas around our living room over six o’clock drinks. We agree that Emerson’s journals, containing almost a million words, are not only by themselves a perfect chronicle of his mind…but are the place where his seedlings are planted, where they germinate, and where they finally flourish. These journals chronicle a thinker’s life, an activist’s life, a man’s life. But there again lies the challenge. How to make a film about words on a page. The answer perhaps is found in Emerson’s essay “The Method of Nature”…that wild ride through his mind, where the sentences seem, sometimes, like a handful of cooked spaghetti thrown against the wall… some strands sticking, some not. “The Method of Nature” appears to be a kind of disjointed madness, but then you realize that Emerson is writing with a sharpness acquired through the achievement of an ecstatic state. Here is the reason I’ve pushed ahead with this impossible film subject. Listen to this sentence (read it aloud); a sentence that will shake your faith in cynicism to its core: “The soul is in her native realm, and it is wider than space, older than time, wide as hope, and rich as love.”

– Michael Maglaras, November 28, 2022