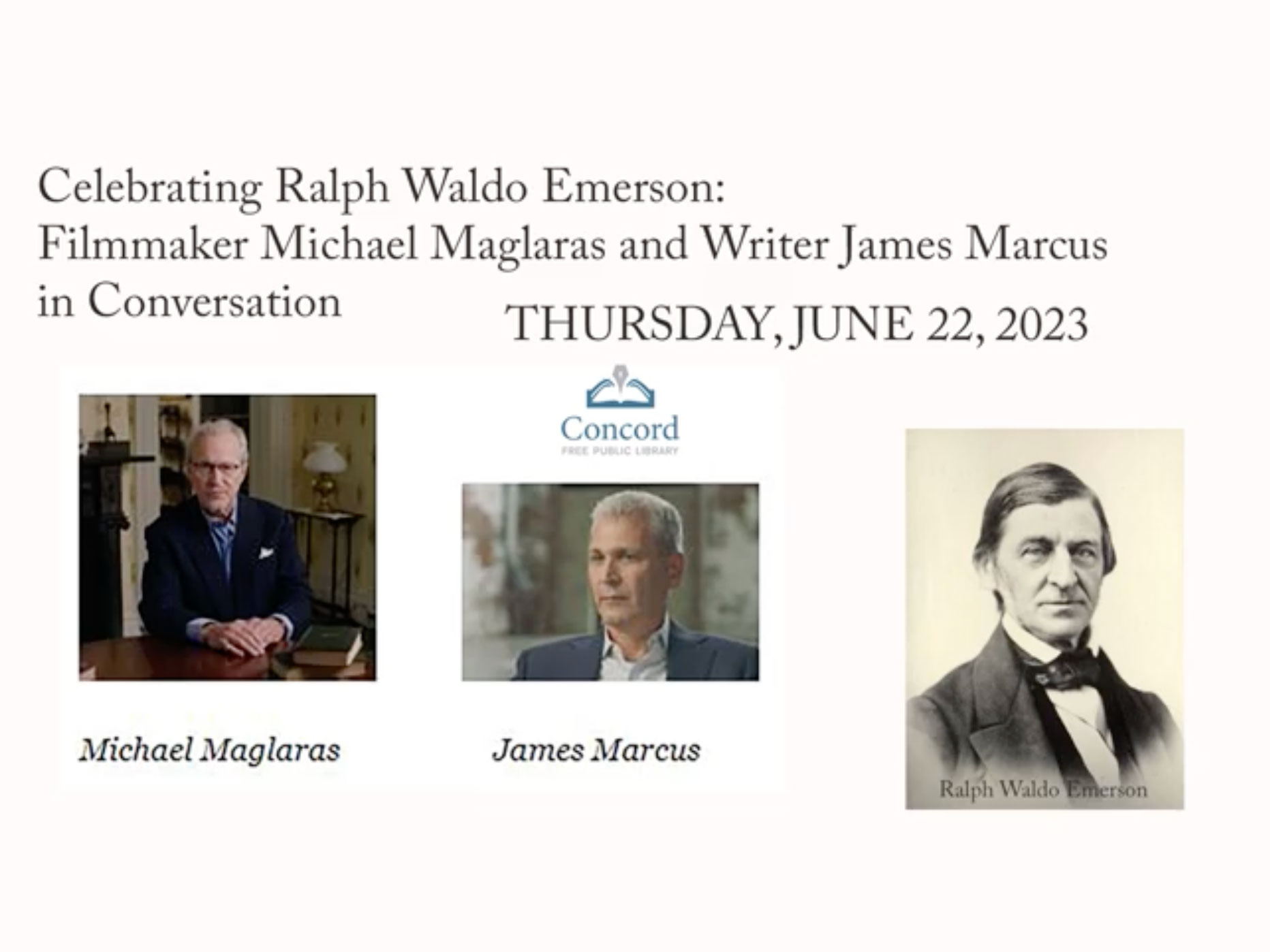

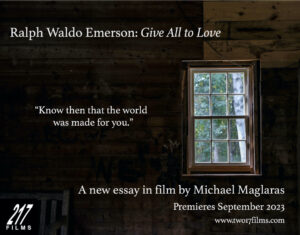

In my upcoming film “Ralph Waldo Emerson: Give All to Love” I try to make the case for Emerson’s fearlessness. For Emerson was in fact fearless. He walked away, early in his life, from security, from comfort…in short, from the ministry of Christ.

It seemed inevitable that Emerson would leave the ministry. Oh, the sermonizing part, he liked that. It resolved his deep need to communicate. But he would never make a conventional Protestant pastor. The sick visits; the social functions; it was just not for him.

What kept him away from the church was dogma and ritual; what drove him away was blood.

Christ’s blood. His late wife Ellen’s blood. Both were more than he could bear. The turning of wine into blood and bread into body. The coughing up of Ellen’s tubercular blood and tissue. He could stand it no longer. It was time to self-destruct his career, his paycheck, his standing in the community.

He told them that at the prestigious Second Church in Boston, where he had been occupying the pulpit as a popular young minister. He told them that he could administer communion no longer. The news was not greeted with enthusiasm. There was a showdown.

But, first, there was to be a bit of breathing room…the church would be undergoing some repairs. A month’s reprieve before this crisis of conscience would need to be settled. He traveled north to the White Mountains of New Hampshire… the redoubtable Mary Moody Emerson joined up with him. He asked her what he should do. The answer was quick and clear: “Do what you need to.”

By July 13, 1832 they were at Crawford Notch. Emerson would write in his journals, “The good of going into the mountains is that a life is reconsidered.”

Reconsidering his life and his future was exactly what this 29-year-old widower was doing. A summer in the White Mountains was the perfect place; a place of total immersion for an entirely questioning moment.

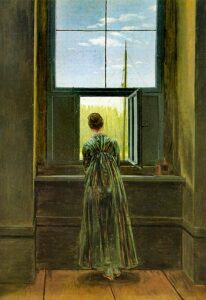

A painter whose work I’m fairly certain Emerson may not have known is the German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich. A painter whose work presents the solitary spiritual adventurer searching for points of connection through immersion and perception among peaks, and valleys, and sudden changes in weather. Back in Boston, Emerson would write in his journal on October 9, 1832 with a new fierce determination, “I will not live out of me. I will not see with others’ eyes. I would be free. I dare to attempt to lay out my own role. Henceforth, please God, forever I forego the yoke of men’s opinions. I will be light-hearted as a bird and live with God.”

And with that statement, conceived under the backdrop of an impeccable New Hampshire summer, Emerson launched with certainty the remainder of his life.

This takes us back to the painting of Caspar David Friedrich. It’s always the subject’s back to us. You think, it’s a kind of maddening depersonalization. But no, that’s not it at all. Emerson would deliver a lecture at Waterville College in Maine in 1841 entitled “The Method of Nature.” This was nine years after his vivid connection with the sublime at Crawford Notch. “The Method of Nature”…not to be confused with his first great essay, simply “Nature”…is a wild ride indeed. An almost hallucinogenic jumble of phrases and sensations. But what writing!

Emerson would write: “I conceive a man as always being spoken to from behind and unable to turn his head and see the speaker. In all the millions who have heard the voice, none ever saw the face.”

He would go on: “O rich and various Man! thou palace of sight and sound, carrying in thy senses the morning and the night and the unfathomable galaxy; in thy brain, the geometry of the City of God; in thy heart, the bower of love and the realms of right and wrong.”

Prose as poetry. Do you see now why Emerson was Emerson, and remains Emerson? If you ever lose hope, you can regain it by reading “The Method of Nature.”

On September 9, 1832, he gave his last sermon at the Second Church as its pastor. It was a farewell. He presented a reasoned, liturgical argument against the ritual celebration of the Eucharist… all that remained was to say “goodbye”. He looked straight out at his parish and said, “It is my desire in the office of a Christian minister to do nothing which I cannot do with my whole heart.”

Well, that took care of his comfortable pulpit job. He would eventually toss his whole pastoral career over the cliff. On July 15, 1838, he was asked to address the six or so young men who were graduating from Harvard Divinity School. Also present were many parents and distinguished faculty. The address started auspiciously and innocently enough. It was when he told these young preachers of the faith, that they were about to embark on a life filled with meaningless ritual, that almost everyone present felt he had lost his mind.

After his resignation from the Second Church, his health compromised, he sailed for Europe on Christmas Day 1832 to regain his strength. He would be gone for ten months. Traveling on to England he would meet the poet Wordsworth, the social philosopher John Stuart Mill, and the man with whom he would enjoy a decades-long pen-pal relationship…the philosopher and historian Thomas Carlyle.

It would be in Paris, though, where he would see something that confirmed in his mind the direction that his heart had already decided he should take.

I have written that Emerson was fearless. Courage was required to be a Transcendentalist. Not the loud and hollow courage that we are used to in our own time, but the quiet courage born of independence of thought and action.

Emerson saw something in Paris that continued the chain reaction of resolve about how he would conduct the rest of his life…a resolution of purpose first arrived at during that summer in the White Mountains.

That resolve would reach the peak of expression in his famous essay from 1841 “The Transcendentalist.” He would write in that essay about that special brand of courage and the type of human being whose quiet but persistent voice we needed to hear then…need to hear now.

“Amidst the downward tendency and proneness of things, wherever a voice is raised for a new road or another statue, for a subscription of stock, for an improvement in dress, or in dentistry, for a new house or a larger business, for a political party, or the division of an estate – will you not tolerate one or two solitary voices in the land, speaking for thoughts and principles not marketable or perishable?”

– Michael Maglaras