At 100, Armory Show is still debated

January 13, 2014

Just over 100 years ago, the Armory Show of 1913 brought European avant-garde art to the forefront of American attention. Two thirds of the show’s art was by American artists, but the other third, by Europeans like Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Cezanne, Henri Matisse and Marcel Duchamp, caused a scandal.

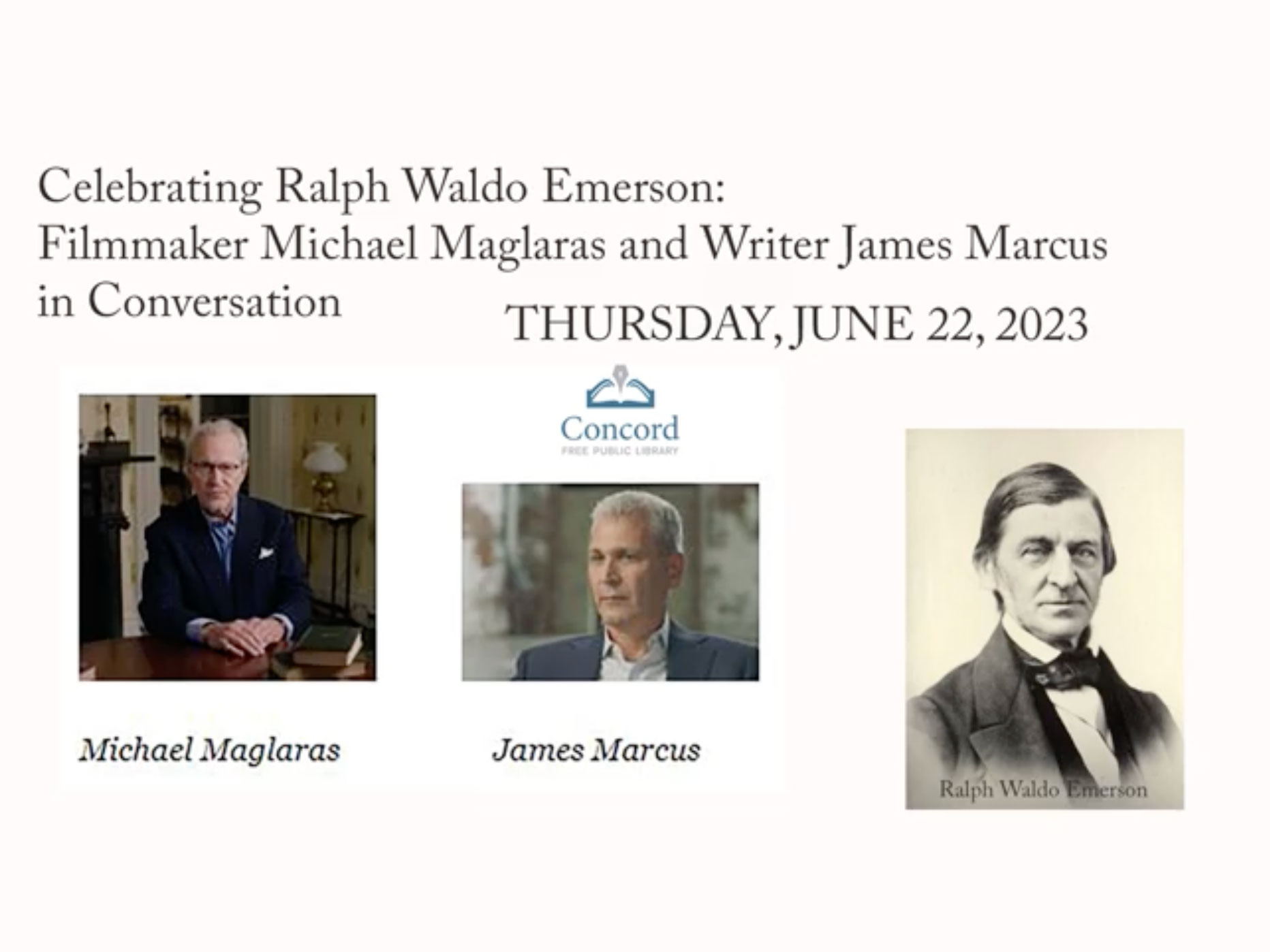

Michael Maglaras’s “The Great Confusion: The 1913 Armory Show” (2013) was screened at the Hood Museum’s Loew Auditorium on Jan. 10 and brought the drama of the original show back to life. In his film, Maglaras, kept from attending the screening by inclement weather, masterfully captures a unique moment in art history and successfully positions it among greater trends in American society at the time.

The show’s conception dated back to 1911, when a group of artist friends met to talk about the prospect of an exhibit that would combine contemporary American and foreign art. This group would become the Association of American Painters and Sculptors, who assembled the show from European works gathered abroad and American works curated at home.

When the final show opened at the New York City Armory on Feb. 17, 1913, it was massive, with 1,300 works by over 300 artists.

After provocative reports about the show’s debut — President Theodore Roosevelt is reputed to have exclaimed, “That’s not art,” referencing some European works — an estimated 87,000 visitors toured the New York show. It later traveled to Chicago and Boston.

The Armory Show featured many experimental American artists, including members of the Ashcan School, an art movement that depicted everyday scenes around New York City. The show’s notable pieces, however, were European.

Most polarizing was Marcel Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2.” The abstract image came to represent a new phase in contemporary art that was entirely new to the U.S.

Art history professor and department chair Mary Coffey said that the show was shocking to Americans for many reasons. The country had strong Puritan roots, which characterized art as a sinful, unnecessary luxury, and lacked institutional support for art development, such as federal and state grants for art projects.

Although New York City was a growing artistic center at the turn of the 20th century, the Armory Show was a “watershed” event, Hood assistant curator for special projects Sarah Powers said. The public was drawn to the exhibit like a “circus attraction,” filled with “strange curiosities,” she said.

The show was defined by its divisiveness. It split artists and the public into two factions: those who were transformed by it and those who resented its emphasis on European art. Many gallery viewers came away confused, feeling somehow duped by what they had seen.

For almost all patrons, it was the first exposure to works that would later be categorized as cubist, fauvist or futurist.

The show prompted “a reconsideration of what art was,” Powers said, which was disquieting to many.

The early 20th century was a time of rapid industrial growth and booming immigration in the U.S. Maglaras captures these changes in his film with clips of the suffrage movement, World War I and the rise of mega cities to properly relay the spirit of burgeoning America.

For Powers, the film’s power comes from putting “the show in its historical context.” In hindsight, some viewers’ negative reactions to the show seem linked to xenophobia and fear of rapid change, she said.

Coffey said that an art critic at the time described the works derogatorily as “Ellis Island” art. Yet with a greater historical view, immigrants were crucial to contemporary art’s evolution in the U.S., she said.

Maglaras’s film and centennial dialogue around the show “helps us to see how fine art becomes the occasion of debate about other social concerns,” she said.

As the 20th century continued to bring about rapid societal changes, subsequent radical art shows were not quite as shocking as the Armory Show, Powers said.

Spanning just 90 minutes, Maglaras’s film explores particular works and the overall effect of the show. Addressing the film’s audience via Skype, the director said he wanted the audience to judge the exhibit and art “for themselves and by themselves.”

Maglaras said that he “wanted to let the art reveal itself,” which he accomplished by panning a work to allow the audience to fully appreciate its details. He would then relay the history of the piece. The strategy simulated being at the exhibit, transported to the past.

Maglaras described the show and its controversy as “beauty … that it is a uniquely American experience.”

Even 100 years after its opening, the Armory Show continues to call for “constant reevaluation of what happened in the past,” Coffey said.

Sally Bellew, a local artist who attended the screening, called this type of study an “overlooked opportunity” to reengage with the works.

The Hood also assembled a number of relevant pieces from its own collection in a small display, such as works by Arthur Bowen Davies and Walt Kuhn, the Armory Show’s original organizers, to complement the film.

Avery Brown ’17, an audience member, visited the installation prior to viewing the film.

“I really enjoyed being able to see works of art by those artists who, moments later, I was able to hear more about in the film,” she said.